For many years, school curricula have limited their scope to the same Black figures throughout history. While lectures on the legacies of Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and Harriet Tubman are all important, some educators (and their students) are eager to learn more about underrepresented trailblazers like Lewis Latimer, Marsha P. Johnson, and Max Robinson.

While there's a push to add more names to the Black history curriculum, states like Florida, Texas, and Oklahoma have approved or suggested measures to limit race-related language in public schools. Others have also banned books by Black authors that focus on race.

Behind these concerning cases of censorship and bans on books lies the controversy over critical race theory. "It is part of what I would call kind of a cycle of anxiety in which book challengers are driven by concerns and fears about a changing world. And so whatever the issue of the day is, then that usually drives and pushes people to try to remove books," Richard Price, author of the blog Adventures in Censorship, told NPR.

Critical race theory is a 40-plus-year-old academic concept that attempts to inspect systemic racism's impact on U.S. laws. Proponents believe that racism isn't biological; instead, it is a societal creation enforced by hierarchies.

Since 2020, there have been 783 anti-CRT bills, resolutions, opinion letters, and other measures introduced in a total of 244 local, state, and federal government entities, according to the University of California, Los Angeles' School of Law's CRT Forward project, which tracks attacks on CRT. In 2023, Florida's decisions regarding school curriculum came under fire when its Department of Education claimed the new AP African American Studies course "lacks educational value" and was indoctrinating students—an accusation the College Board deemed slanderous.

Despite the pushback on school curricula, many districts continue to push for Black history. As forgotten names come to the surface, Stacker used news articles and documents to shine a light on 19 groundbreaking Black historical figures whose names might be lost in the fight for more robust Black history education. Read more to find out how the lives of these figures shaped society today.

Bettmann // Getty Images

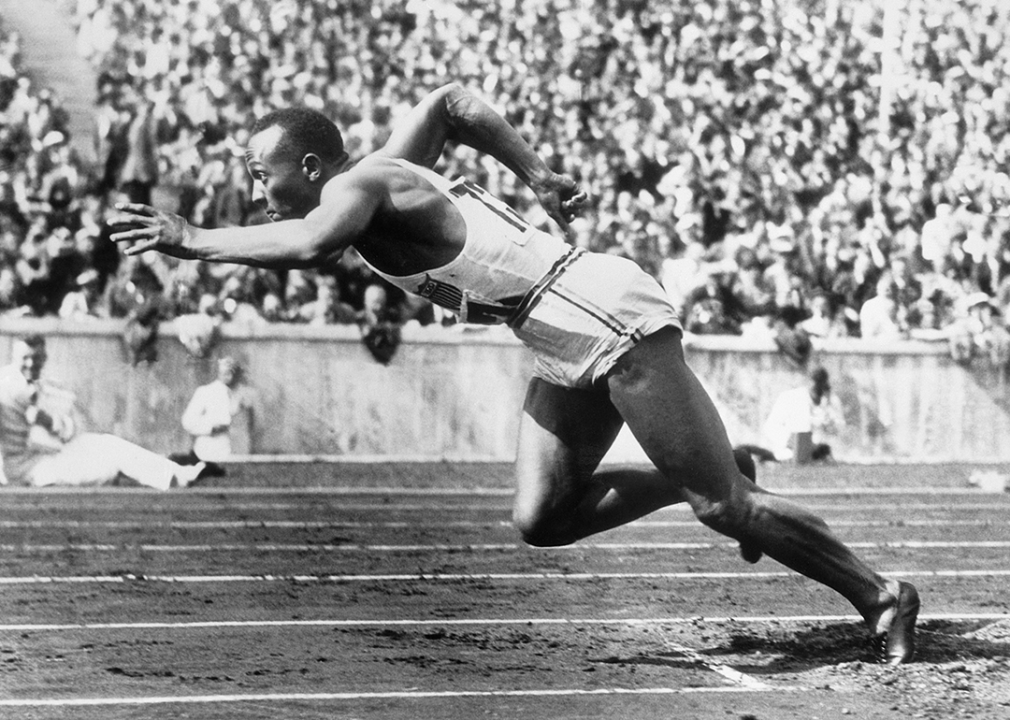

Jesse Owens

Jesse Owens, also known as "The Buckeye Bullet," started his track career in high school, setting records for the long jump, the 100-yard dash, and the high jump. After graduating, Owens enrolled at Ohio State University to continue his wins in events like the Big Ten, Amateur Athletic Union championships, and the Olympic trials.

In 1935, Owens competed and won 42 events. His growing fame led him to the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, where he secured four gold medals and broke two Olympic records, including the record for long jump, an achievement he held for 25 years.

However, as a Black man, he experienced racism when he returned to the United States. He was neither invited to the White House nor received honors by President Franklin Roosevelt. It was not until 1976 that President Gerald Ford awarded Owens the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

WESTOCK PRODUCTIONS // Shutterstock

Eunice Carter

In 1935, Eunice Carter uncovered evidence connecting a mafia boss to a prostitution operation. Carter's efforts led to his conviction.

Carter was the first Black American woman to work as a Manhattan District Attorney Office prosecutor. Initially, she struggled to get a private practice, but it wasn't until 1935 that she was brought on to special prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey's team to curb mob activity.

Carter was able to find that women arrested for prostitution were represented by the same lawyers and bail bondsmen who had connections to the most powerful racketeer in the country, Charles "Lucky" Luciano. She continued to build a case that led to brothel raids and, eventually, the sentencing of Luciano in 1936.

She worked under Dewey until 1945, when she started her private practice. Carter later went on to aid the United Nations and the National Council of Negro Women until she died in 1970.

Space Frontiers // Getty Images

Mae Jemison

Women and astronauts of color have Mae Jemison to look up to as the first Black American woman to embark on outer space. Before joining NASA, Jemison worked as a general practitioner after receiving her master's in medicine from Cornell University in 1981. She later conducted medical research with the Peace Corps in Sierra Leone and Liberia.

Jemison always had a goal of flying into space, and when she returned to the United States, she applied to NASA's astronaut training program and was accepted in 1987. Five years later, Jemison and six other astronauts flew Space Shuttle Endeavour into space on mission STS-47 on Sept. 12, 1992. There, she spent eight days conducting experiments on bone cells.

After leaving NASA, Jemison formed her own company researching advanced technologies for developing countries. She is part of the National Women's Hall of Fame and the National Medical Association Hall of Fame.

New Africa // Shutterstock

Marie Maynard Daly

Marie Maynard Daly became the first Black American woman awarded a doctorate in chemistry in the United States. She earned her bachelor's in chemistry from Queens College and fellowships to pursue her master's at New York University. She received her doctorate in 1947 from Columbia University, becoming the first Black woman to earn such an honor in any subject at the university.

Despite the racial and gender biases, Daly conducted pivotal studies on cholesterol, sugars, and proteins. In 1955, she returned to Columbia to collaborate on innovative rat studies measuring cholesterol levels and blood pressure to indicate the correlation between high cholesterol and clogged arteries, which can cause stroke or heart attack. Her research also extended to the damage smoking can have on lung health in both humans and dogs exposed to chronic cigarette smoke.

Beyond her research, Daly advocated for enrolling more Black students in medical school and graduate science programs, spearheading recruiting and training efforts for Black students at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Susan Biddle/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Dorothy Height

Dorothy Height was a civil rights and women's rights activist devoted to improving opportunities for Black women. While working for the national YMCA office, Height oversaw the desegregation of all YMCA chapters in 1946. She was also the first director of the Center for Racial Justice.

Height's 40-year presidency of the National Council of Negro Women made her a leading figure in the Civil Rights Movement, and she is also credited as the first person to relate equality issues for Black Americans and women, seeing relationships in both sectors that were often deemed separate.

Height received numerous honors for her contributions, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal.

John Pineda // Getty Images

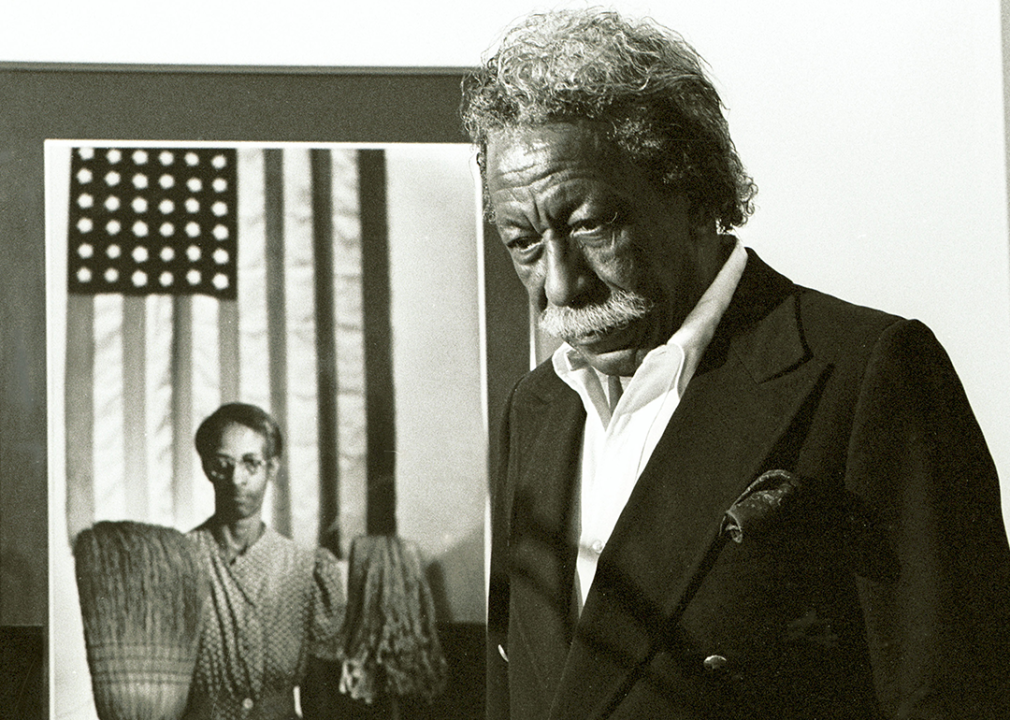

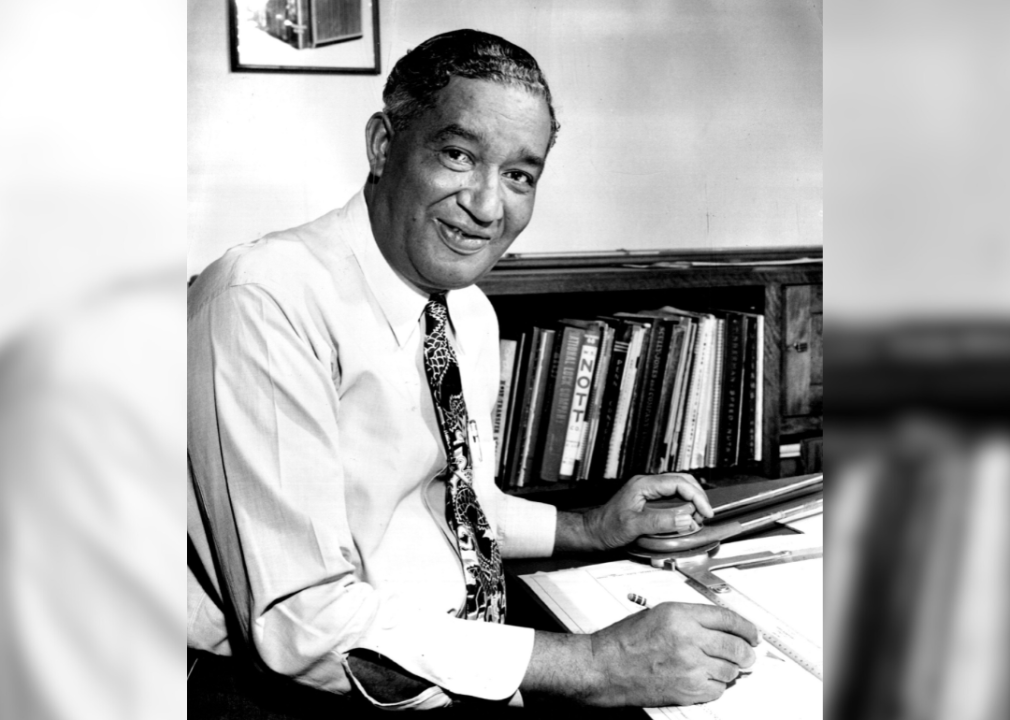

Gordon Parks

From the 1940s to the 2000s, Gordon Parks' photojournalism focused on poverty, civil rights, race relations, and urban life. Parks was also a well-known composer, author, and filmmaker who interacted with influential people.

In 1949, he became the first Black staff photographer at Life magazine. Twenty years later, he tried his hand in Hollywood, becoming the first Black American to direct a major Hollywood studio feature film, "The Learning Tree," based on his semi-autobiographical novel.

Parks also published numerous books, including memoirs, novels, poetry, and photographic tomes. His work can be found in major art museums nationwide, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

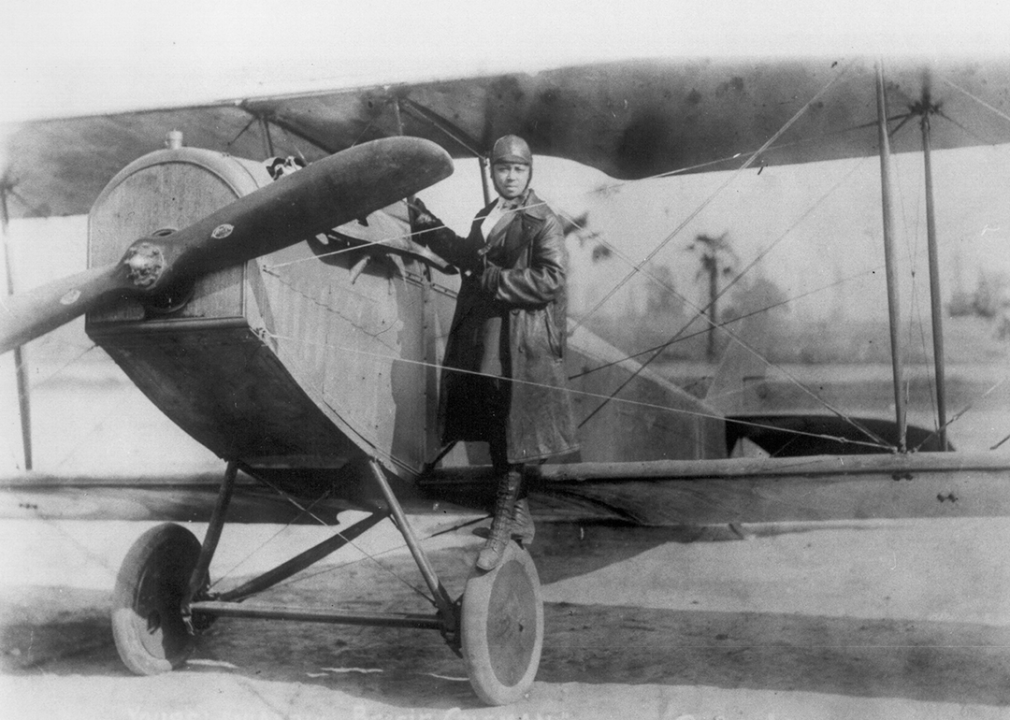

Bessie Coleman

Bessie Coleman was the first Black American woman to hold a pilot's license. At a time when Black people were prohibited from voting, using public facilities, and riding railway cars with white people, Coleman dreamed of learning to fly, inspired by the stories her brothers came home with after serving during World War I.

After many rejections from aviation schools in the United States, Coleman applied to and was accepted at the Caudron Brothers School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, France. In 1921, she received her international pilot's license and returned to the U.S., where she performed numerous air shows. Coleman used her popularity to encourage other Black Americans to fly and pointedly refused to perform at locations that didn't allow entry to Black audiences.

Patrick A. Burns/New York Times Co. // Getty Images

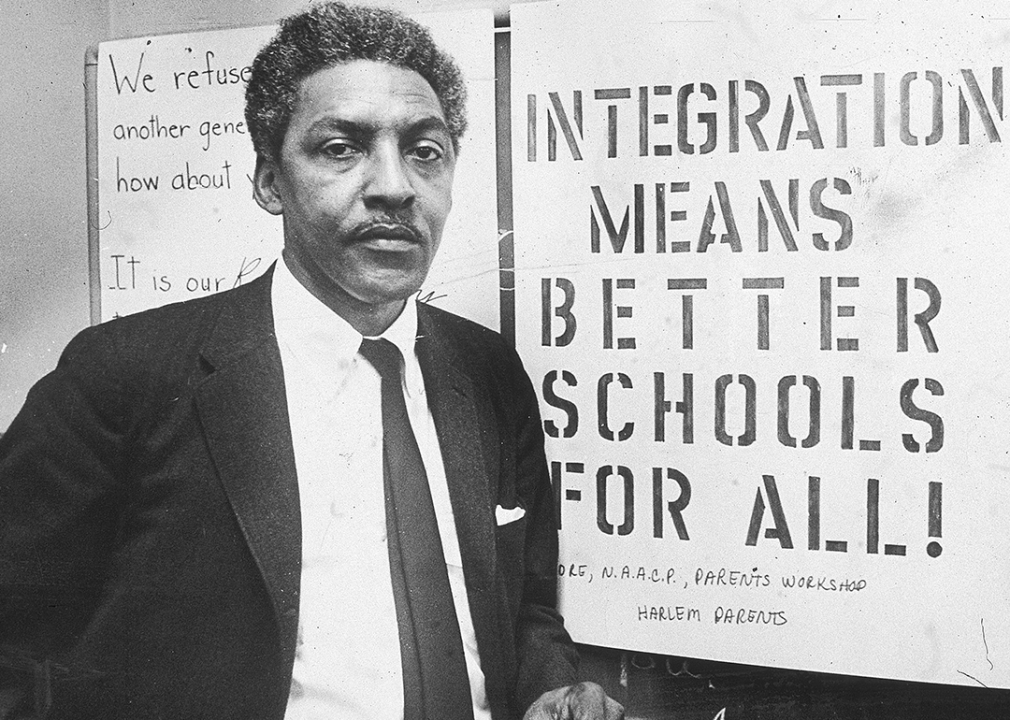

Bayard Rustin

The 1963 March on Washington is known for Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech, but Rustin worked alongside A. Philip Randolph as deputy director and logistical planner for the historic event. Rustin further assisted King with the boycott of segregated buses in Montgomery, Alabama.

As a leader of social movements for civil rights, socialism, and nonviolence, Rustin espoused the philosophy of nonviolent resistance, profoundly shaping King's views on the subject as well. And while his contributions have often been overlooked because he was an openly gay Black man when homosexuality was considered a mental illness, history has come around since then.

Rustin was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013.

Afro American Newspapers/Gado // Getty Images

Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander

Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander was the first Black woman lawyer in Pennsylvania. Alexander studied at the University of Pennsylvania, earning her Ph.D. in economics in 1921, becoming the first Black woman to do so.

After passing the Pennsylvania bar in 1927, she joined her husband's law firm, working on family and estate law. Alexander eventually opened her own firm in 1959 when her husband was stepped up to become a judge for the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas.

In 1947, President Harry Truman appointed her to serve on his Committee on Human Rights. In 1978, President Jimmy Carter appointed her as the head of the White House Conference on Aging, a position she held until 1981. Alexander continued practicing law until her retirement in 1982.

Barbara Alper // Getty Images

Marsha P. Johnson

The LGBTQ+ movement would not be where it is today without Marsha P. Johnson. One of the most prominent figures of the movement in New York City, Johnson tirelessly advocated for LGBTQ+ youth without housing, people living with HIV and AIDS, and equal rights for LGBTQ+ people.

At 17, Johnson moved to New York City from New Jersey, where she could more freely express her identity and sexuality through drag. Johnson was one of the first drag queens to regularly patronize Greenwich Village's Stonewall Inn after it opened its doors to women and drag queens.

Johnson was at the front lines of the Stonewall riots of 1969. Like many transgender women and LGBTQ+ people of the time, Johnson was fed up with the oppressive policing she and her peers experienced and led multiple protests after the event. These riots would be a key milestone in the gay liberation movement.

Since the protests, Johnson has become a guiding light in the LGBTQ+ community. She was a member of the Gay Liberation Front as well as co-founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries—which focused on supporting LGBTQ+ people experiencing homelessness—with friend and fellow trans rights activist Sylvia Rivera.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Jane Bolin

Jane Bolin was the first Black American woman graduate of Yale Law School and the first Black American woman judge in the United States. After graduating from Yale, Bolin worked with her family's practice before moving to New York. She continued to break barriers as the first Black American woman to work at New York's corporation counsel office.

Once sworn in as a judge of the city's family court in 1939, she changed segregationist policies, requiring child care agencies receiving public funding to accept children no matter their race or ethnicity. Bolin served for 40 years and retired at 70. Even after retirement, Bolin continued working with children, volunteering to tutor at New York City public schools and serving on the New York State Board of Regents.

Microgen // Shutterstock

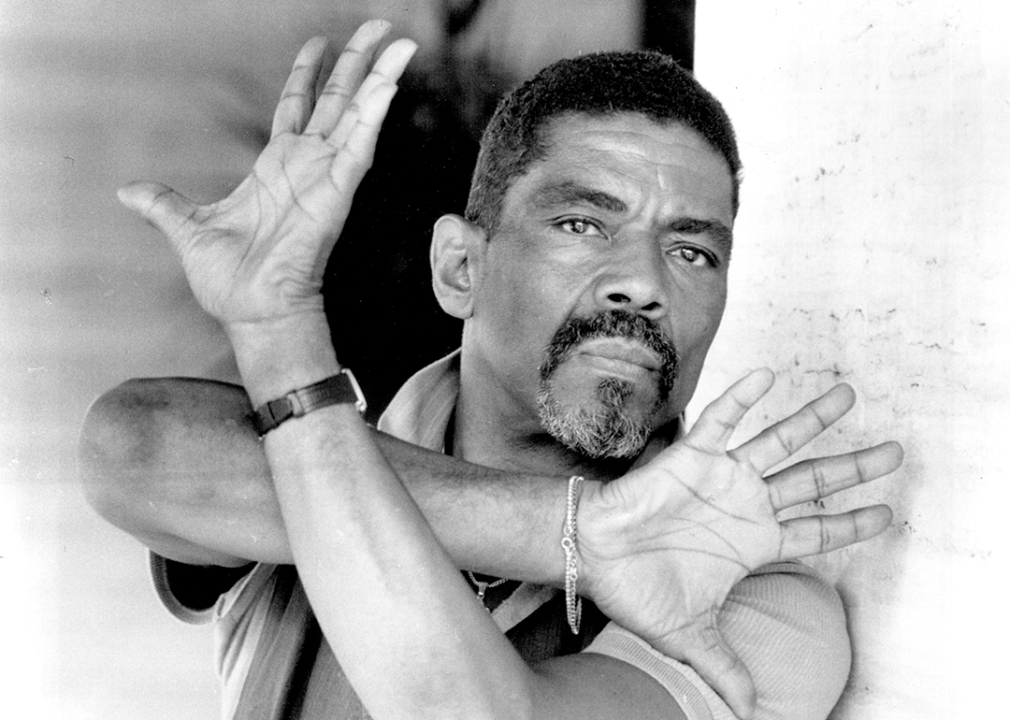

Max Robinson

There are many firsts when it comes to Max Robinson. Robinson was a journalist for ABC News and co-anchored for "ABC World News Tonight," becoming the first Black American broadcast network news anchor in American television history in 1978.

In 1959, he moved to Washington D.C., where he covered urban neighborhood issues and racial issues. He obtained six awards for his coverage of the 1968 race riots following Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination. He also won two regional Emmys for a documentary he created on Anacostia called "The Other Washington," where he exposed the racist laws keeping the Black community in that neighborhood in poverty.

He reached the peak of his career as a part of a three-person team on "World News Tonight," anchoring alongside Frank Reynolds in Washington and Peter Jennings in London.

Sharee Marcus/Star Tribune via Getty Images

Frederick McKinley Jones

Frederick McKinley Jones was interested in mechanics at a young age, which he used as an auto mechanic. With limited education, Jones taught himself mechanical and electrical engineering.

During World War I, he served in the U.S. Army, repairing machines and equipment. After returning from the war, McKinley continued to educate himself on various technologies, including electronics, when he caught the eye of entrepreneur Joseph Numero.

Besides working on innovations that helped convert silent-movie projectors into talking projectors, McKinley also found ways to enhance picture quality. By the late 1930s, Jones developed portable refrigeration to help the U.S. military carry food and blood during World War II. That same technology also helped distribute fresh food and vegetables throughout the country year-round.

With Numero's help, Jones founded Thermo King Company (now Thermo King), which made over $1 million in sales by 1997, when Ingersoll-Rand Company acquired it. He became the first Black American elected to the American Society of Refrigeration Engineers in 1944. Jones gained over 60 patents throughout his career, including one for a portable X-ray machine, and was posthumously awarded the National Medal of Technology in 1991.

Betsy Graves Reyneau/Three Lions/Hulton Archive // Getty Images

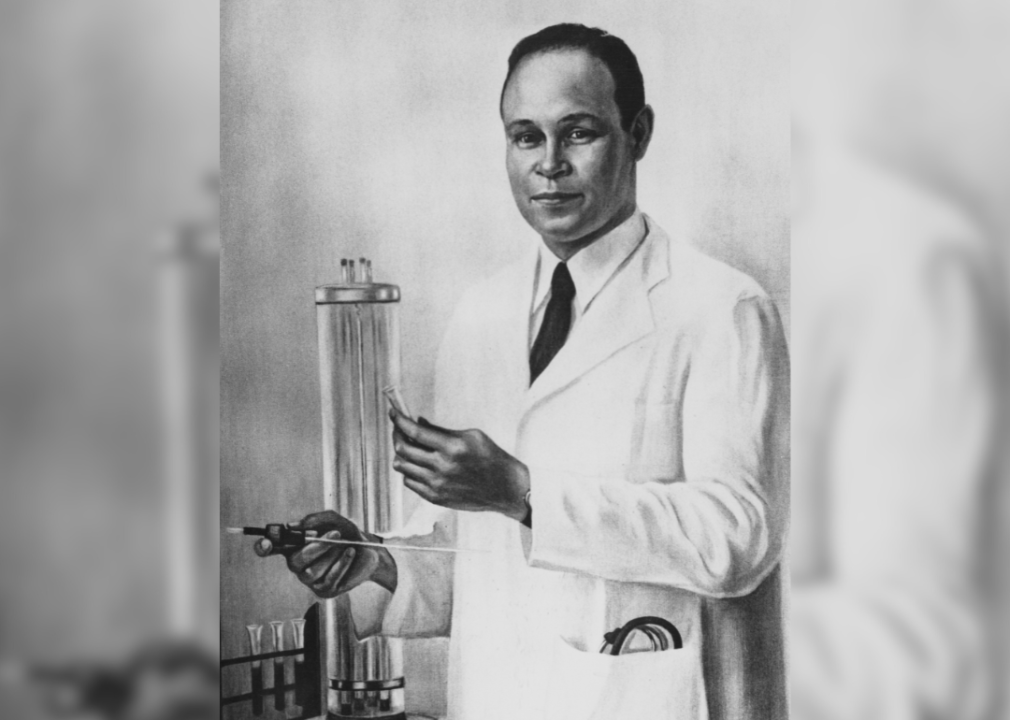

Charles R. Drew

Charles R. Drew, better known as the "father of the blood bank," is a pioneer in blood chemistry research. Drew conducted original research in fluid replacement and held a trial blood bank for seven months. In 1940, he became the first Black American to earn a doctorate in medical science from Columbia for his thesis, "Banked Blood: A Study in Blood Preservation."

Drew was also pivotal in developing procedures for extracting plasma, preserving it against contamination, and packaging it for wounded soldiers during World War II. Through a U.S. relief program called Blood for Britain, more than 14,000 blood donations were collected, and 5,000 liters of plasma were shipped to England under Drew's direction. Many recognized his achievements, earning him a Spingarn Medal from the NAACP.

Fotosearch // Getty Images

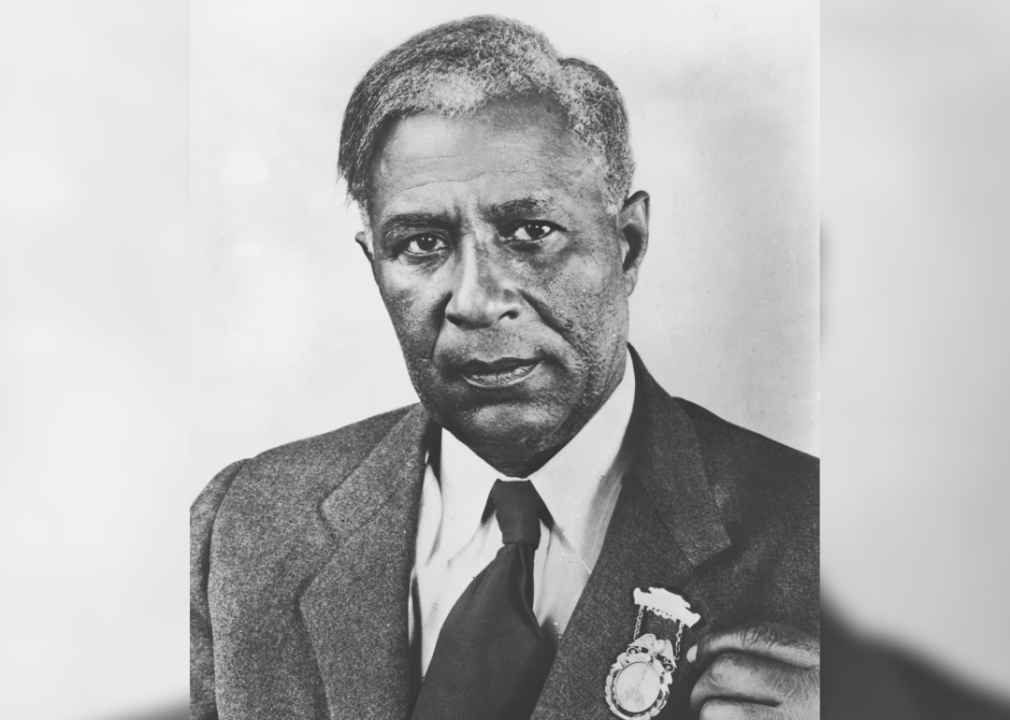

Garrett Morgan

Inventions like the traffic signal are best attributed to trailblazers like Garret Morgan. Morgan started his career working for a clothing manufacturer, where he learned about fixing equipment, leading to a patent for a sewing machine belt fastener. After handling a successful business, Morgan created a breathing device to protect wearers from smoke, gas, and other pollutants. The device earned him the first prize at the Second International Exposition of Safety and Sanitation.

Safety is a theme that runs through Morgan's inventions. In 1923, he patented a new traffic signal. Before his invention, traffic lights were manually operated and had only two modes—stop and go. Morgan added a third mode—a caution light—to prepare motorists to change gears. General Motors purchased Morgan's patent for $40,000 in 1923 (about $710,000 today).

NYPL/Interim Archives // Getty Images

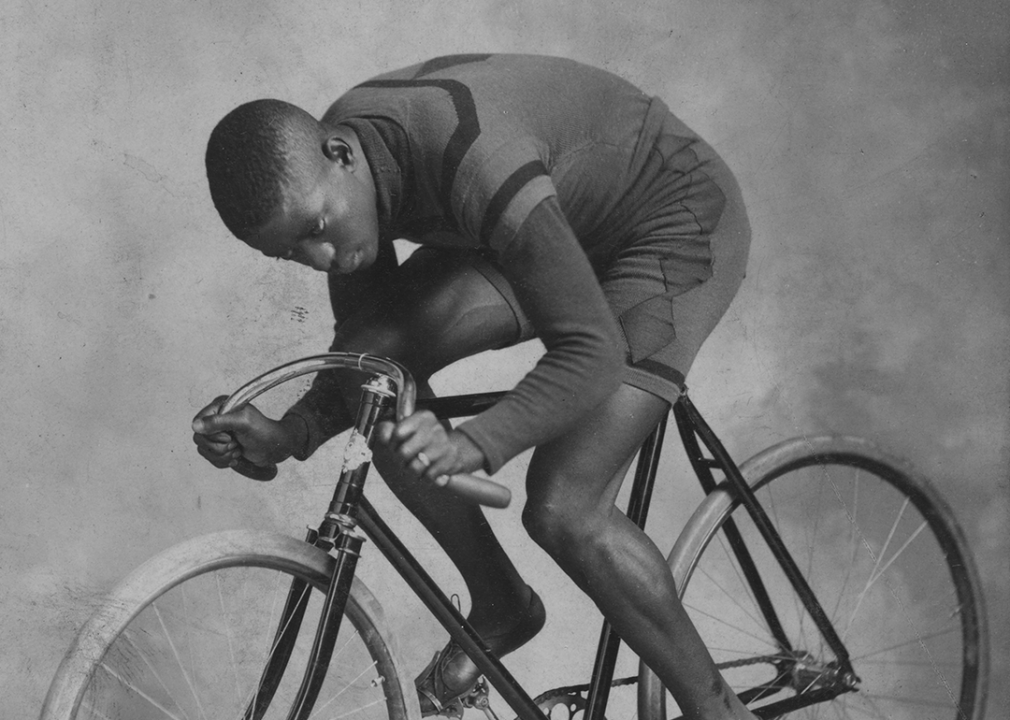

Marshall 'Major' Taylor

Before Jackie Robinson, Jesse Owens, and Jack Johnson, there was Marshall "Major" Taylor. Taylor was the first Black American sports sensation to take an interest in cycling. At an early age, he received a bicycle and was later hired to perform cycling stunts outside a bicycle shop.

By 1898, he had seven world records and was named the national cycling champion two years later. At his peak, he was touring internationally and was one of the highest-paid athletes of his time.

Taylor continued to face racism even at the height of his achievement. He was barred from some races, turned away from establishments, and even subjected to insults. He died in poverty and was buried in an unmarked grave. His remains were found and relocated in the 1940s by fellow bicycle professionals. His name was also added to the United States Bicycling Hall of Fame in the 1980s.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Althea Gibson

Before Serena and Venus Williams, there was Althea Gibson. Gibson was the first Black American tennis player to compete in the U.S. National Championships (a precursor of the U.S. Open) in 1950. She was the first Black American to win a Grand Slam title in 1956, winning the French Championships; the following year, she became the first Black American to triumph at Wimbledon.

She showed a love for tennis at an early age, but there weren't many opportunities for Black people to pursue the sport then. However, she loved playing local paddle tennis. Her skills eventually got her noticed, leading to her being professionally trained in tennis.

Gibson continued to gain attention and win tournaments, leading to her famous string of firsts (discussed above). Between 1956 and 1958 alone, she was in 19 major finals, winning 11. Gibson retired in 1958 but pursued another sport: golf. She became the first Black American woman to join the Ladies Professional Golf Association tour. Gibson was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1971.

Robert Pearce/Fairfax Media via Getty Images

Alvin Ailey

Alvin Ailey's choreographies are an important part of modern dance history. His most famous dance, "Revelations," used traditional African American blues, work songs, and spirituals to tell inspirational stories of persistence from slavery to freedom.

In 1958, Ailey founded the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, which gained popularity along with his dances, leading to a tour sponsored by the Department of State. Other notable works included 1958's "Blues Suite" and "Cry," which featured a woman solo created for his mother. He also created works set to jazz music greats like Duke Ellington and Hugh Masekela.

In his career, he choreographed 79 ballets. In 1988, Ailey was honored by the Kennedy Center for his contributions to dance. In 2014, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Universal History Archive // Getty Images

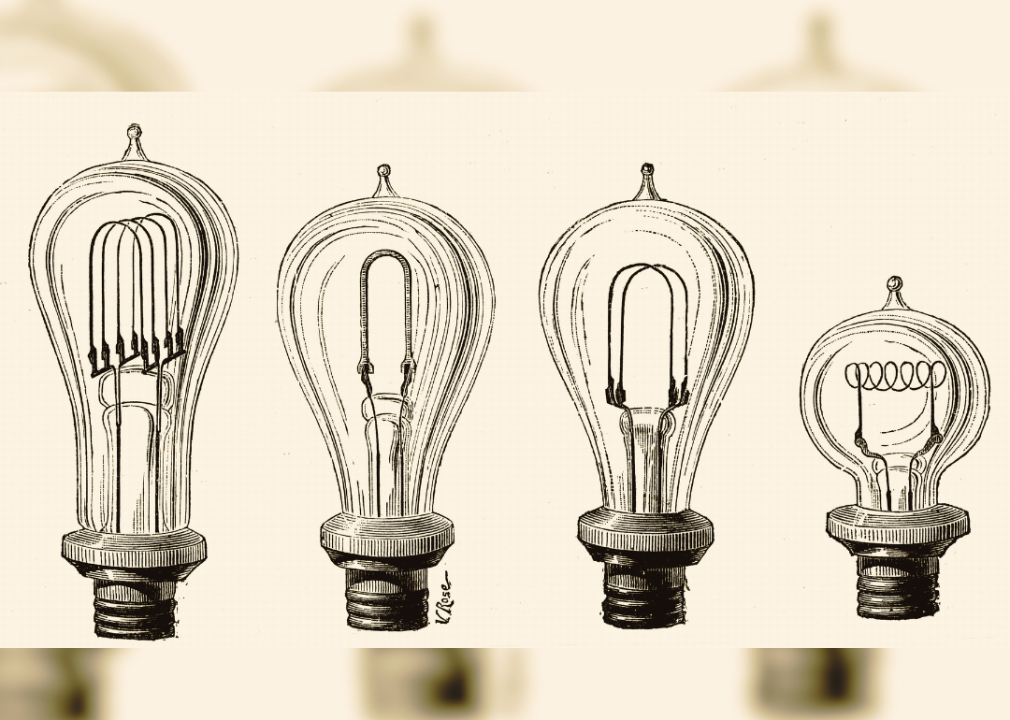

Lewis Howard Latimer

As the son of self-emancipated people, Lewis Howard Latimer created his own path through mechanical drawing. He observed drafters at work and read books during his job as an office boy for a patent law firm. His eagerness to learn the trade earned him opportunities to work on important projects like the telephone, lightbulb, and an early version of an air conditioner.

He was a critical reason that Alexander Graham Bell was awarded the patent for the telephone, working late into the night drafting blueprints and efficiently submitting an application hours ahead of Bell's competitor. A filament he developed made Thomas Edison's lightbulb more reliable and long-lasting. Latimer also pursued creative interests like poetry, playing the flute, and speaking enough French to oversee electrical lighting installations. He was awarded 10 U.S. patents.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close.