By JohnEric W. Smith, Associate Professor of Exercise Physiology, Mississippi State University

Less than a month into North America’s official summer, heat waves were blistering much of the West. California and the Southwest faced excessive heat watches for the second time, after a mid-June heat wave pushed temperatures above 100 F (38 C).

And in late June an intense heat dome settled over the Pacific Northwest for four days, setting all-time temperature records in Oregon, Washington and British Columbia. The effects were most evident in Lytton, British Columbia, which reported a temperature of 121 F (49.5 C) on June 29, far above its average high for the date of 76 F (24.4 C). A day later, the town was engulfed by a wildfire.

As an exercise physiologist, I know that the human body is an amazing machine. But like all machines, it functions effectively and safely only under certain conditions.

People frequently debate whether wet heat in places like Florida or dry heat in desert locations like Nevada is worse. The answer is that either setting can be dangerous. Hot desert climates are stressful due to extreme temperatures, while humid subtropical climates are stressful because the body has trouble removing heat when sweat doesn’t evaporate readily. As recent events have shown, hot is hot.

North America has a wide range of climates, but when people talk about heat, they often compare the Southwest and the Southeast. Some communities in the Southwest’s hot desert climates, such as Las Vegas, have average summer high temperatures over 100 F (38 C), with relative humidity typically around 20%. This means the air is holding about one-fifth of the maximum amount of moisture it can hold at that temperature and pressure.

In contrast, Southeast locations like Orlando, Florida, typically have average temperatures around 90 F (32.2 C), with humidity regularly approaching 80%. Looking only at temperature, the desert clearly is hotter on average.

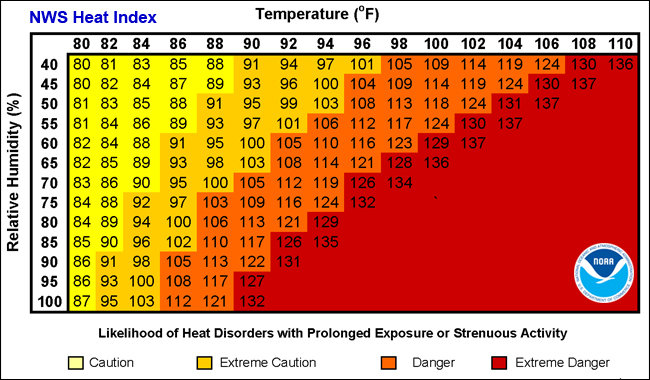

However, it’s also important to consider how heat affects the body. Weather reports often do this using the heat index, which calculates how the human body perceives conditions factoring in humidity as well as heat.

Sweating is your body’s primary way of cooling you off. When sweat evaporates away from your skin, it takes heat with it. But when humidity is high, the air already holds a lot of moisture, so the sweat remains on your skin. As it saturates clothing and drips from the body, it can remove only a small amount of heat compared with the cooling that comes with the evaporation of sweat.

As a result, when we account for humidity, the heat exposures people experience in Las Vegas and Orlando are very similar.

As people go through their daily lives, their bodies work continuously to maintain a temperature close to a normal level of about 98.6 F (37 C). In regions that regularly experience high heat stress, such as the Southeast and Southwest, most buildings and homes now have air conditioning, which helps people maintain healthy temperatures.

But in areas where heat is unusual, such as the Pacific Northwest, many buildings and residences lack cooling. As a result, people are exposed to higher heat for longer periods of time during events like the region’s late June heat wave than they would be in regions where hot weather is the norm.

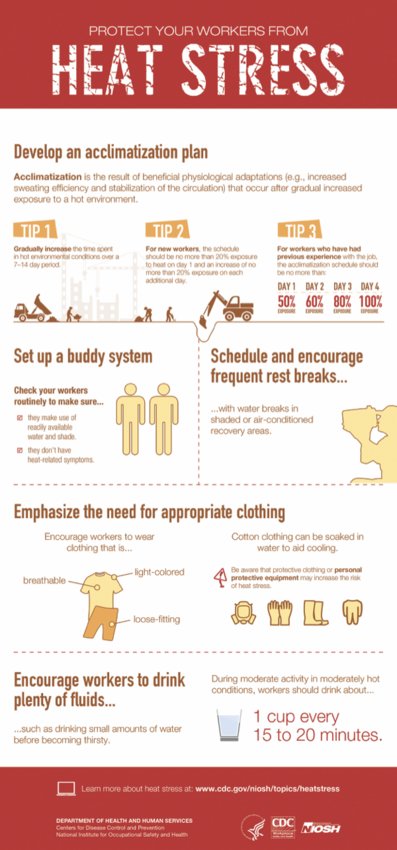

Just as buildings and residences in areas chronically exposed to heat are equipped with ceiling fans and air conditioning, bodies that are regularly exposed to heat can acclimatize, or adapt and improve their ability to cool. This starts to occur with the first heat exposure – for example, the beginning of fall sports practices in August – but take weeks of regular exposure to reach maximal levels.

One of the first things our bodies do in adapting to heat is to produce more plasma – the watery portion of blood. This enables our circulatory systems to move heat to the skin more effectively so that sweating can remove it from the body.

We also begin sweating earlier than people who are not acclimatized to heat, and our maximal sweat rate increases. These adaptations improve our bodies’ ability to dissipate heat to the environment.

Behavior changes are another way of adapting to heat stress. Since midday is typically the hottest part of the day, it makes sense to avoid physical work and exercise then. When people are active, their bodies break down nutrients – carbohydrates, fats and protein – into energy. This powers movement and also generates metabolic heat, which adds to the body’s heat stress.

Taking advantage of shade is another important strategy. Heat radiating from the Sun adds to the stress produced by warm air temperatures. Staying in the shade can significantly reduce the external heat load on people who have to be outdoors during hot spells.

Many of the hundreds of deaths and hospitalizations that experts have attributed to the recent heat dome in the Northwest probably reflect that buildings there were less equipped to keep people cool than in hotter regions, and residents were less acclimatized to heat.

A healthy adult body can acclimatize to heat, but older people and children are less able to adjust. As people age, their cardiovascular systems change in ways that cause them to pump blood less effectively. This reduces the body’s ability to move heat to the skin to be transferred to the environment.

Children and older adults may also have less active sweat responses, which can reduce their potential to cool off through sweating.

Humans can tolerate most areas of the Earth, but extreme heat requires extra steps. If there’s a heat wave in your local forecast, seek out shade and begin to acclimatize by increasing your activity gradually when things get too hot. Drink more fluids to account for increased fluid loss from sweat, while also making sure not to overhydrate. And avoid outdoor activity during the hottest hours of the day if possible.

Whether heat waves are humid or dry, they are health threats that everyone should take seriously.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here